This Black History Month, we encourage you to make your own journey — whether with loved ones or alone — to pay homage to these historical settings of bravery, community and resilient love. We hope that being in the presence of these significant sites resonates deeply and helps develop a greater appreciation of and love for the Loudoun we call home today.

The following text is adapted from Deborah A. Lee’s book, “Honoring Their Paths: African American Contributions along the Journey Through Hallowed Ground” (2009) and from the Loudoun County Government’s website. Many thanks to The Journey Through Hallowed Ground Partnership and the Loudoun County Parks, Recreation and Community Services Department for sharing these important elements of Loudoun County’s history.

Photo courtesy of Loudoun Department of Economic Development

Aldie Mill Historic District (Aldie, VA)

In the antebellum period, enslaved and free people of color worked at Aldie Mill and in the vicinity. Wavin Corum, a free black entrepreneur, hauled goods and cut cordwood for mill operators. Daniel Dangerfield was an enslaved “mill boy,” hired to the owner of a mill near Aldie, before he escaped to Pennsylvania where his capture, fugitive slave hearing, and release in 1859 fanned sectional animosity in both states.

After the Civil War, African Americans established communities near Aldie, building Mount Pleasant Baptist Church (1875) and a school. Women founded the Housekeepers’ Club in 1914 for fellowship and learning, and it still meets today.

Goose Creek Rural Historic District (Lincoln, VA)

In the antebellum period, Goose Creek was a center of Underground Railroad activity. During the Civil War, most residents of the area remained loyal to the Union. During Reconstruction, with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau, they built a stone school for black children. African Americans established two religious congregations in the village of Lincoln — one of which (Mount Olive) still has an active congregation.

In 1890, freedman James Hicks led in founding the Loudoun County Emancipation Association, established to commemorate Emancipation Day and work for racial uplift. In addition to civic leader, Hicks was an astute farmer, tradesman, and businessman. By 1900 he had clear title to a house and farm on Lincoln Road and a cobbler’s shop and orchard in nearby North Fork. In 1911 he also owned a house in Lincoln. His lifelong lobbying and petitioning efforts demonstrated his vision and commitment to education and equality.

Loudoun County Courthouse (Leesburg, VA)

Three brick courthouses—dating from 1761, 1811, and 1895—have served Loudoun County on this same site. Slave auctions were once held on the steps. Today the building is recognized for its role in the struggle for freedom and equality. The National Park Service designated the Loudoun County Courthouse as an Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site because two free black men, Leonard A. Grimes and Nelson T. Gant, were tried here for helping women and children escape from slavery.

In 1883, African Americans petitioned for their rights and, fifty years later, Charles Hamilton Houston became the first African American attorney to argue a major case in a southern courtroom. Houston became known as “the man who killed Jim Crow,” as his legal strategy led to Brown v. Board of Education and the Supreme Court decision that segregated schools were not equal.

Loudoun Museum (Leesburg, VA)

Black-owned businesses once flourished in the building now occupied by the Loudoun Museum. In the 1920s Nathan Johnson operated a butcher shop; it later became a restaurant called the Dew Drop Inn. Patrons climbed the stairs inside to visit a beauty shop and a doctor. Other buildings that stood along the block were black-owned.

Loudoun Museum collections feature letters exchanged in the 1830s between brothers Mars and Jesse Lucas in Liberia and their emancipators in Purcellville, brothers Albert and Townsend Heaton. Exhibitions include African American history, such as information on John W. Jones, who escaped from slavery in Loudoun County and became a prominent Underground Railroad stationmaster in New York.

Photo courtesy of Virginia Department of Historic Resources

Middleburg Historic District (Middleburg, VA)

African Americans were among Middleburg’s earliest inhabitants; as enslaved or free laborers and skilled craftsmen, they built many of its structures, tilled the soil on surrounding farms, and tended its livestock. In fact, Loudoun County’s most dramatic escape from slavery began near Middleburg on Christmas Eve in 1855, led by Frank Wanzer.

Much community life centered around the town’s two churches, Asbury Methodist, built in 1829 and assumed by African Americans in 1864, and Shiloh Baptist, whose congregation organized in 1867 and built the present structure in 1913. A Freedmen’s Bureau office was located on the corner of Marshall and North Jay streets, which became known as Bureau Corner, anchored by the Grant School. By the 1930s and 1940s, the town was largely African American.

For the town’s centennial in 1987, resident Johnnie T. Smith recalled a score of black-owned businesses from that era, including a barbershop, two beauty shops, restaurants, a pool hall, three taxicabs, three general contractors, a tailor, chair caner, and a blacksmith shop. Maurice Edmead Sr., M.D., treated some white as well as black patients. William Nathaniel Hall, the largest general contractor in Loudoun County and the only one licensed and bonded, built the original Middleburg Bank, a new wing on the Leesburg hospital, and reconstructed George Washington’s Gristmill. Middleburg local, John Wanzer, served as president of the County-Wide League of parents, teachers, and others whose activism resulted in the successful initiative for a full and accredited high school for black youth in 1941.

Photo courtesy of Judith McGuire

Oatlands (Leesburg, VA)

Throughout its history under private ownership, great numbers of enslaved and free African American workers shaped and cultivated the gardens, tilled fields and cared for livestock. They also tended the house and furnishings, cooked and served meals to the estate owners and their numerous guests, drove carriages and automobiles and supported the socially-prominent owners, from the Carters to the Eustises.

Some of Oatlands’ bondmen and women bravely eloped to the North in search of freedom. In recognition of these freedom seekers — such as William Jordan Augustus, who fled Oatlands in 1809 — Oatlands is a site in the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program. After the Civil War and general emancipation, some African Americans in Loudoun County migrated north and west, but many of those who worked at Oatlands, such as Basil Turner, chose to remain and established the community of Gleedsville nearby. Turner helped shepherd the estate through four tenures and was even married there in 1871.

Photo courtesy of Purcellville Music and Arts Festival

Purcellville Historic District (Purcellville, VA)

Purcellville’s black community developed on the south side of the town along G Street, known to most residents as “the Color Line.” In 1910, the Loudoun County Emancipation Association (founded in Hamilton) bought ten acres on the corner of A and 20th Streets and established Lincoln Park. They built a tabernacle, organized Emancipation Day Celebrations, and hosted baseball games, Horse and Colt Shows, Field Day, ministers’ conventions, and a host of other events. Choreographic genius and Purcellville native, Billy Pierce, even went on to work with Fred Astaire and create dances such as the Charleston and Black Bottom — significant cultural contributions to the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1919 residents formed a Willing Workers Club that borrowed money, purchased land, and built a school. They established a library there, too, since they were banned from the “public” library. In 1942, residents constructed Grace Annex Methodist Church. In 1948, Loudoun County built the larger brick Carver Elementary School that educated black students in the area through the seventh grade. Long used only for storage after the public schools were fully integrated in 1968, the beloved school reopened as a senior center in early 2007.

Photo courtesy of Waterford Foundation

Waterford Historic District (Waterford, VA)

Slavery and freedom rubbed shoulders in Waterford. The settlement was founded by Quakers opposed to slavery, but slaveholders also lived in the vicinity and conducted slave trade in the village. In the early nineteenth century, free blacks migrated to Waterford for work in the mill or tannery, to ply other trades such as blacksmithing and coopering, or to work on Quaker farms. Black women performed domestic work and practiced as midwives, delivering babies black and white. Some free blacks bought homes themselves in the village.

During the Civil War, Waterford sympathized with the Union and organized a federal cavalry unit, the Loudoun Rangers. At least one free black man of Waterford, Daniel Webster Minor, joined as an auxiliary, and several other Waterford men of color fought in other Union regiments. In 1866, just after the war, African Americans, with the help of Quakers, bought a lot and erected a building they used as a church and school. From the 1870s until 1957, it was a Loudoun County Public School. In 1891, after years of meeting in the school, black Methodists built John Wesley Church on Main Street overlooking the mill.

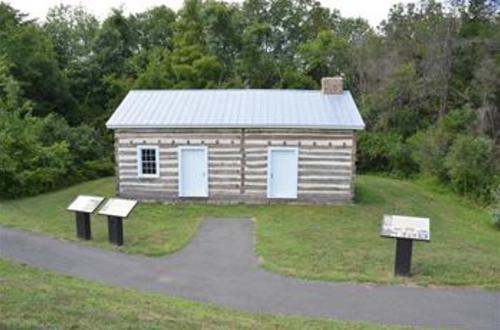

Photo courtesy of Loudoun County Parks, Recreation and Community Services Department

Settle-Dean Cabin (South Riding, VA)

Charles W. Dean worked as a slave for Thomas Settle in the Village of Conklin in eastern Loudoun County for many years. The two families inhabited a house consisting of two log cabins sided-over with boards and joined together. Mr. Settle willed the 142-acre property to Dean and his descendants in 1886.

The house was in extremely poor condition when Toll Brothers acquired the property, located in what is now South Riding, in the 1990s. Despite the condition of the structure, members of the local community urged the Board of Supervisors to save the building. A subsequent proffer agreement was reached requiring the developer to dismantle the original log house and relocate it a few hundred feet on the west side of Loudoun County Parkway.